The Honest Guide to Camping Around Reine

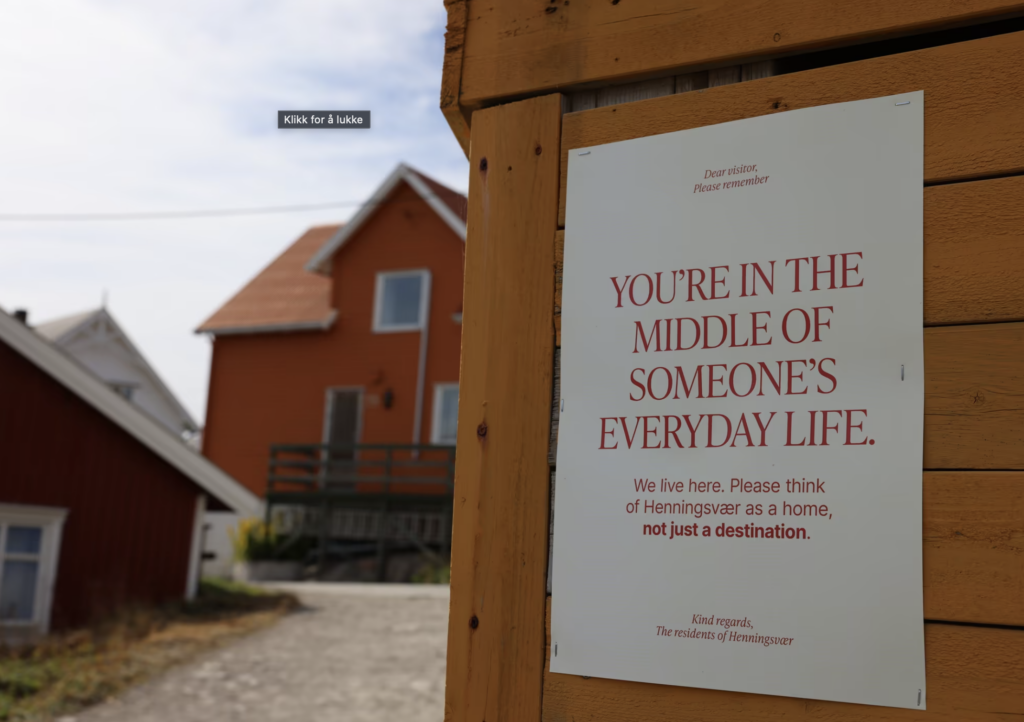

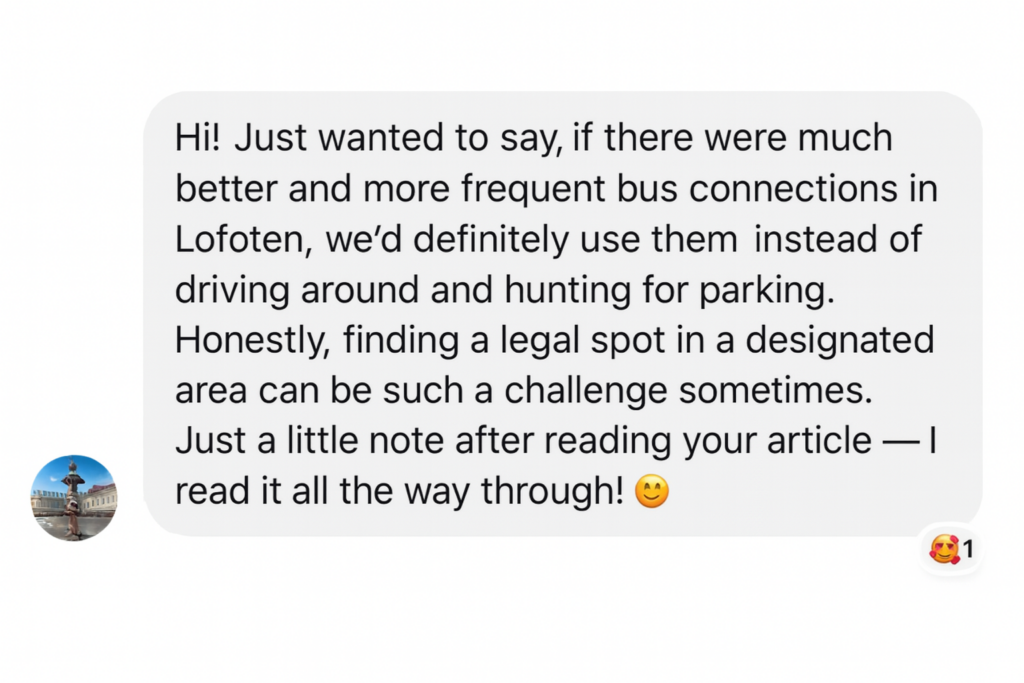

Norway is marketed as a camping paradise. Thanks to the right to roam (allemannsretten), you can still sleep outside of designated campsites, which is pretty amazing. People come here with dreams of fjords, freedom, and falling asleep under the midnight sun.

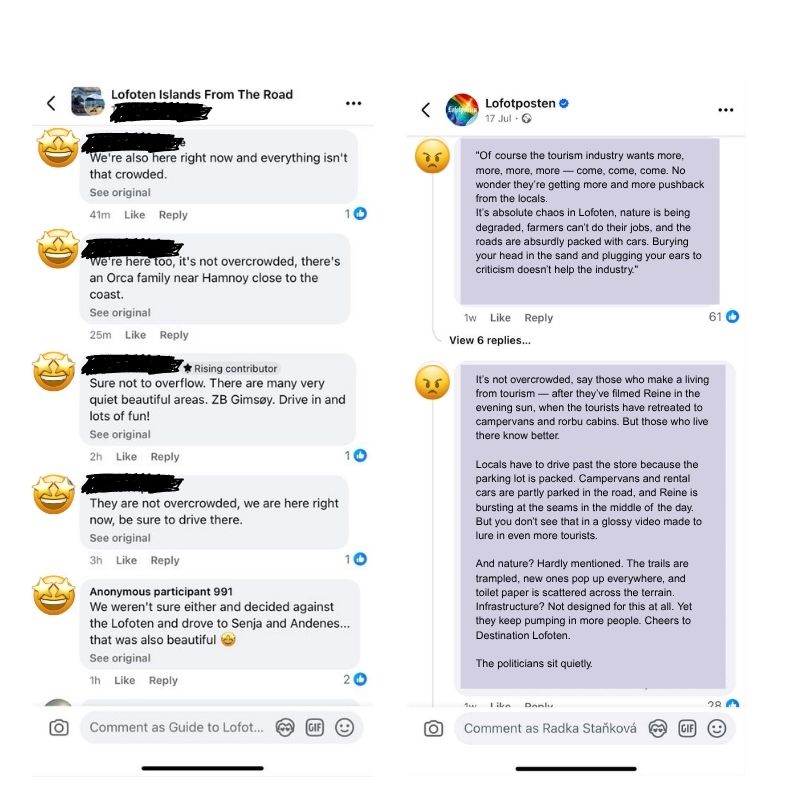

Lofoten takes that dream and cranks it up to eleven. It’s stunningly beautiful—almost offensively so—and it’s no surprise