Whale Watching in Norway in Summer

Summer Whale Watching on Svalbard

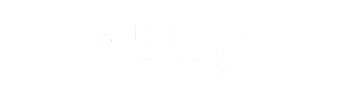

Between May and September, you can spot blue whales, fin whales, humpbacks, minkes, and even belugas around Svalbard, with most day trips departing from Longyearbyen.

If you’re up for a longer adventure, you might even see High Arctic species like narwhals, belugas, and bowhead whales on extended multiday expeditions from Longyearbyen.

Summer Whale Watching in Vesterålen

Apart from Svalbard, the Vesterålen region—specifically Andenes and Stø—is the only place in mainland Norway where you can go on commercial whale-watching trips during the summer season.

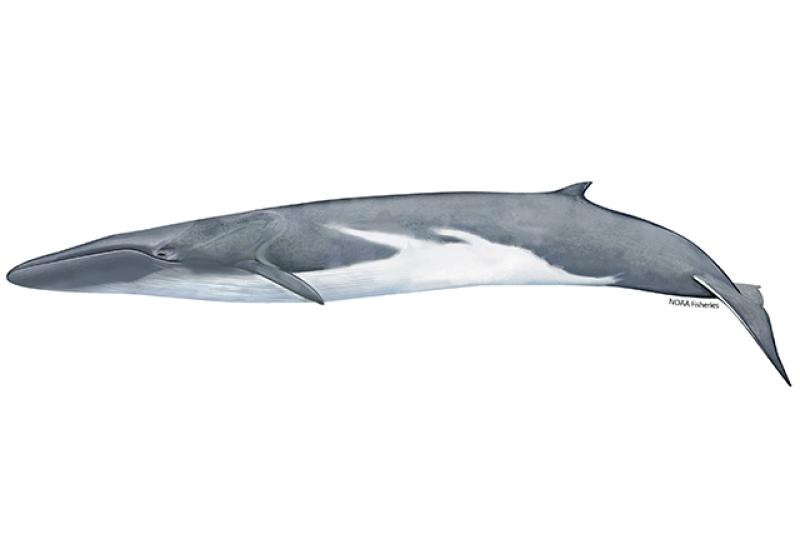

These locations are near the continental shelf, where the ocean floor drops off quickly, creating ideal conditions for deep-diving whales like sperm whales to hunt for squid.

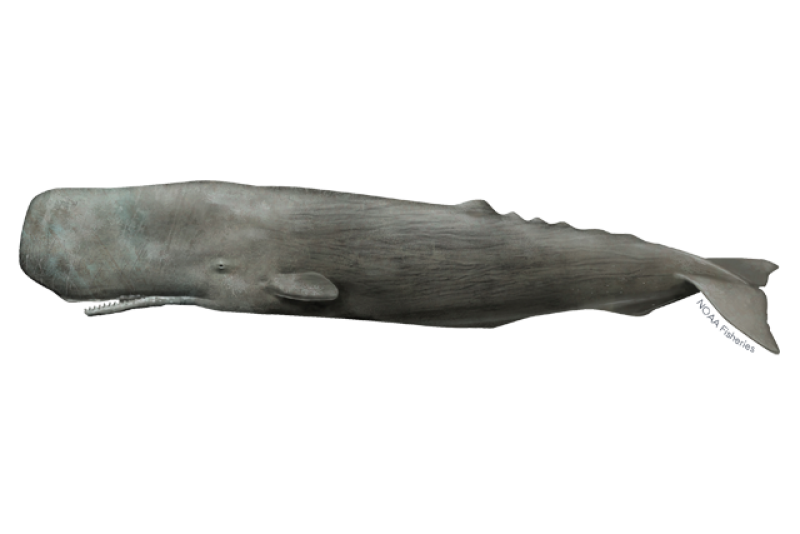

During summer, sperm whales are the main attraction, though you might also see minke whales, pilot whales, and occasionally humpbacks. Because the deep waters are close to shore, it doesn’t take long for the boats to reach prime whale-watching spots.

Whale Watching and Whaling Season in Norway

Whale watching in Norway is an incredible way to see these majestic animals in their natural habitat. In winter, whales head into the northern fjords around Tromsø and Skjervøy, chasing herring.

Meanwhile, Vesterålen offers year-round whale watching, with Andenes being a top spot due to its proximity to the continental shelf.

But, alongside all the whale watching, there’s also something you might not expect—a whale hunting season. From April to September, Norway is one of the few countries that still hunts whales commercially, focusing mainly on minke whales.

History of Whaling in Norway

Whaling has a long history in Norway, dating back to the Viking Age, when whales were hunted for their meat, blubber, and bones. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Norway developed into one of the world’s leading whaling nations.

Modern whaling began in the mid-1800s with the invention of the explosive harpoon, allowing for more efficient hunting of large whales.

Phasing Out of Whaling for Other Species

In the mid-20th century, whale populations began to decline due to overhunting, and international concerns about the sustainability of whale populations grew.

Norway continued whaling but faced increasing international pressure to reduce catches, especially as global awareness about whale conservation increased.

This led to several key steps in the phase-out of whaling for larger whale species:

🐋 1973: CITES

Norway signed the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), which restricted the trade of endangered species. Under CITES, species are listed in three appendices, with Appendix I offering the highest level of protection.

Whale species listed under Appendix I (species threatened with extinction) included Blue whales, Fin whales, Sei whales, Humpback whales, and Sperm whales. The trade in minke whale products was still permitted under certain restrictions.

🐋 1982: Global Moratorium

The International Whaling Commission (IWC), established in 1946, is the global body responsible for whales’ conservation and whaling regulation.

By the early 1980s, many whale species had been pushed to the brink of extinction due to overhunting, leading the IWC to vote for a global moratorium on commercial whaling in 1982.

The moratorium came into effect in 1986 and applied to all whale species, effectively banning commercial whaling worldwide.

Countries Who Defy International Moratorium on Commercial Whaling

🇳🇴 Norway

Norway formally objected to the moratorium and resumed commercial minke whaling in 1993 under its own national regulations. Norway continues to set its own quotas for minke whale hunts, claiming the practice is sustainable and scientifically managed.

🇮🇸 Iceland

Iceland initially objected to the moratorium but later withdrew from the IWC in 1992. In June 2023, the Icelandic government temporarily suspended whaling for several months due to concerns over animal welfare violations, following reports that some whales suffered immensely after being harpooned.

Iceland’s last active whaling company, Hvalur, received a one-year license in 2024 to hunt up to 128 fin whales. However, as economic and ethical pressures continue to mount, there’s speculation that this may be the final whaling season.

🇯🇵 Japan

Japan continued whaling under the guise of “scientific research,” exploiting a loophole in the IWC regulations. Japan argued that its hunts were for scientific purposes, but the meat from these hunts often ended up in markets.

In 2019, Japan officially withdrew from the IWC and resumed commercial whaling.

Why Are Minke Whales Still Hunted?

Despite the global moratorium on whaling, Norway continues to allow commercial hunting of minke whales. There are several reasons/excuses that the Norwegian state uses to justify the whaling of minke whales.

🐋 Cultural Tradition

Whaling is deeply rooted in Norway’s coastal culture, particularly in the north, where it has provided a source of food and livelihood for centuries. Many Norwegians see minke whale hunting as an important part of their heritage.

🐋 Sustainable Quotas

Norway argues that the minke whale population in the North Atlantic is stable and that hunting quotas are based on scientific data to ensure sustainability. The government sets annual quotas, which it claims align with maintaining healthy populations.

🐋 Niche Market and International Exports

Despite declining demand for whale meat, it remains a niche market, particularly in northern regions and among tourists. Whale meat is still served in restaurants and sold in markets, and government subsidies continue to support the industry. Norway has also exported minke whale meat to Japan, Iceland, and the Faroe Islands.

Current Whaling Practices in Norway

As of 2024, Norway remains one of the few countries that continues commercial whaling, focusing primarily on minke whales.

These hunts occur between April and September, mostly in the Norwegian Economic Zone and around Svalbard and Jan Mayen.

The quota is set each year, and it’s usually between 500 and 1,000 whales, though the actual number caught is often lower. The Norwegian government has set a quota for the hunting season, allowing the killing of up to 1,157 minke whales (2024).

The year’s whaling season has now ended, and figures from the Norwegian Fishermen’s Sales Organization (Norges Råfisklag) show that 414 minke whales were caught. This year’s season is the worst ever. In 2019, 429 animals were caught, which was the worst at that time.

The current estimate for the Northeast Atlantic minke whale population, which Norway mainly targets, is around 89,000 individuals based on data collected between 2008 and 2013. The species is classified as “Least Concern” by the IUCN, meaning it’s not considered endangered, which Norway uses to justify its hunts.

However, whaling remains controversial both within and outside Norway. While whale meat consumption has declined domestically, with only about 2% of Norwegians eating it regularly, the practice persists, partly supported by government subsidies.

Much of the whale meat is marketed to tourists, who support the industry by purchasing whale products.

How Climate Change and Overfishing Impact Whale Safaris in Northern Norway

When you’re out on a whale safari in northern Norway, the experience is directly linked to herring migration—whales follow the herring, their main food source.

But here’s the catch: the migration route of the herring has shifted several times over the years, directly impacting where whales can be seen.

A Short History of Overfishing Herring

Norwegian spring-spawning herring has been the biggest fish stock in the North Atlantic for ages, and it’s been a major source of food for Norway, Russia, Iceland, and other European countries. Herring fishing has been vital to these economies for centuries, especially in the 18th and 19th centuries, when it was processed and traded all over Europe.

But things changed in the 1950s and 1960s. With new tech like bigger boats and better gear, fishing took off like never before. Catch levels shot through the roof, which sounds great, right? Except that by the early ’60s, this massive overfishing led to the collapse of the herring stock—it almost disappeared by the late ’60s.

The collapse of herring stocks in the ’60s is one of the biggest examples of overfishing in the North Atlantic. The situation was so bad that the herring took over two decades to recover. It only bounced back after strict fishing regulations and international agreements were put in place to better manage the migratory stock.

Climate Change Impact on Whale Watching in Northern Norway

Fast forward to recent years, and climate change plays a bigger role. As ocean temperatures rise, herring seek out cooler waters, causing their migration routes to move northward. This has resulted in herring, and the whales that follow them, overwintering further and further north.

In the 1990s, the whales used to overwinter in Tysfjord, about 250 km above the Arctic Circle. But over time, both herring and whales moved along the coast of Vesterålen and Senja to Tromsø and now to Skjervøy.

This change in herring migration is largely due to warming waters pushing herring out of their traditional habitats in search of cooler temperatures. As the herring shift north, the orcas and humpbacks that rely on them for food follow closely behind.

Each time the herring change course, it impacts whale migration and, by extension, tourist whale-watching opportunities.

The Uncertainty Ahead

Now, the big question is: How long will the herring and whales keep coming to Skjervøy?

With climate change continuing to warm the oceans, it’s uncertain whether Skjervøy will remain the ideal overwintering spot for herring and whales. As temperatures rise, the herring may move even further north, which could eventually shift whale migration to more remote areas.

Whale Watching in Tromso: Conclusion

🐋 Whale watching in Tromso and Skjervoy offers an incredible chance to see orcas, humpbacks, and other species in their natural habitat during the herring migration. The whale watching season in northern Norway is between late October/early November and January/early February.

🐋 The movement of whales is tightly connected to the migration of herring, which has shifted over the years due to a mix of overfishing and climate change. This has moved the whale-watching hotspots northward, raising questions about where they might migrate next.

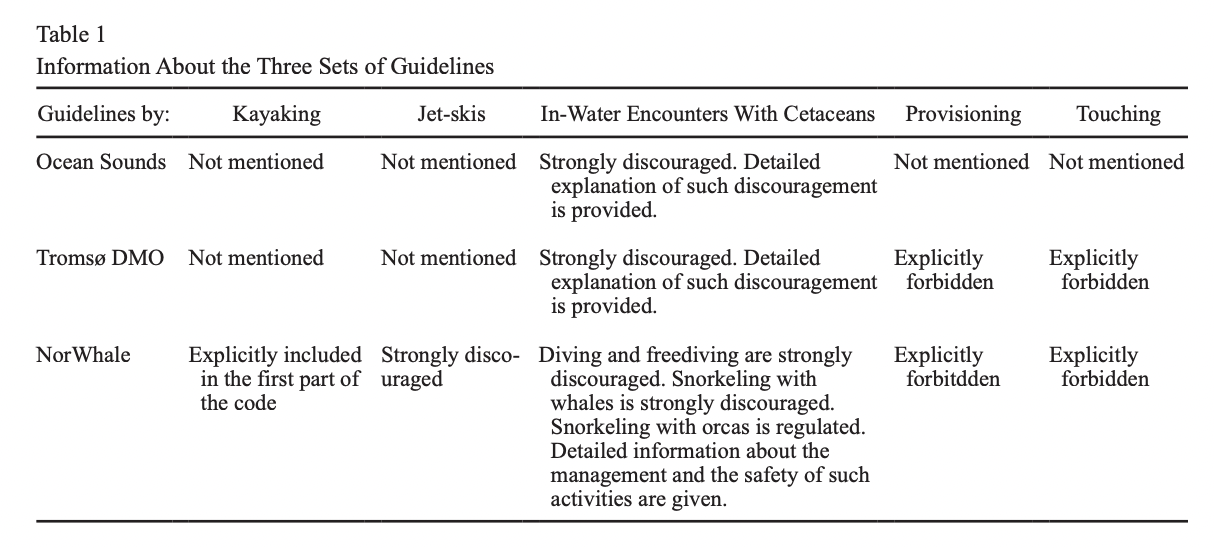

🐋 There are plenty of whale safari operators out there, but not all of them play by the rules. It’s worth doing your homework to find ethical operators who respect the whales and follow the guidelines—because not all of them do.

🐋 Snorkeling with orcas sounds epic, but the real risk isn’t just the orcas themselves—it’s also the chaotic, unregulated tours that make it dangerous for both people and whales. Stricter regulations would be a game-changer for everyone involved, but for now, you’ll need to be extra careful when picking a tour and consider if you really want to take part in this.

In short, whale watching in Tromso/Skjervoy is an unforgettable experience, but make sure you do it in an ethical and responsible way.

Sources

Winter Whales Book by Audun Rikardsen: A book by a renowned researcher and photographer, available in English in many local souvenir shops.

Article: Climate change and the migratory pattern for Norwegian spring-spawning herring—implications for management by Elin H. Sissener and Trond Bjørndal.

Article: Norway’s Orca Tourism: https://oceansaroundus.com/norways-orca-tourism-chaos-in-the-fjords/

Article: Bertella, G. (2019). Close Encounters with Wild Cetaceans: Good Practices and Online Discussions of Critical Episodes. Tourism in Marine Environments, 14(4), 265-273. DOI: 10.3727/154427319X15719407307721

Article: Pagel, C. D., Waltert, M., Scheer, M., & Lück, M. (2021). “Swimming with wild orcas in Norway: Killer whale behaviours addressed towards snorkelers and divers in an unregulated whale watching market.” In: M. Lück, M. & C. Liu (Eds.)